Freight

Virgin Hyperloop takes a new route, but is freight just a pipe dream?

Pyramid schemes: a look into Egypt’s megaprojects

Virgin Hyperloop’s announcement of a bold pivot away from passenger service to a freight-only model, has raised questions as to how it can challenge an already efficient rail freight sector. Luke Christou looks into the move, and asks: is this the beginning of the end for the company?

S

ome 18 months ago, Virgin Hyperloop became the first company to transport people via hyperloop, a high-speed transportation system that involves propelling floating pods through low-pressure tubes at proposed speeds of up to 760mph.

But the US firm’s passenger venture appears to have reached its final stop. In February, it was announced that almost half of Virgin Hyperloop’s workforce was being made redundant, with the company to refocus on delivering a cargo version of its experimental transport system.

Brightline senior vice president, corporate affairs, Ben Porritt

Responding to demand

Speaking to the Financial Times, Virgin Hyperloop stated the pivot was due to “global supply chain issues” caused by the pandemic, and that it was responding to strong demand for cargo services.

With global freight systems overburdened and demand only set to increase, this new mode of transport promises greater speed and efficiency that could help to ease the burden, and at lower costs than air or ship transport. According to digital shipping platform Eurosender, hyperloop freight could be eight times more cost-effective than transporting goods via air.

Evidently, there is some sense in Virgin Hyperloop’s decision. However, the feasibility of passenger transport is also likely to have played a part.

“There are significant issues with putting a person into a capsule, inside a vacuum environment, and travelling at very high speeds, which affects the commercial viability of these systems,” Dr Gavin Bailey, principal consultant and sustainable transport lead for the independent consultancy firm Eunomia, says.

Operators must consider the comfort and safety of their passengers, for instance. Elon Musk’s proposed hyperloop line between Los Angeles and San Francisco proposed a limit of no more than 0.5 g-forces (gs), despite tests having found nausea occurs if 0.2gs is exceeded.

With new technology, there will inevitably be accidents. Of course, freight gets damaged but nobody gets injured.

Even at 0.5gs, a past study by the Transport Research Laboratory established that hyperloop pods travelling at 760mph with a maximum deceleration of 0.5gs would require approximately 80 seconds between pods, allowing 45 departures an hour or up to 1,800 passengers – putting capacity at significantly less than the proposed California high speed rail.

But proving hyperloop technology’s commercial viability will first require various engineering challenges to be overcome, such as tube depressurisation, cornering and maintaining the vacuum - with even small mishaps potentially resulting in catastrophe.

“With new technology, there will inevitably be accidents. Of course, freight gets damaged but nobody gets injured,” Richard Geddes, professor and founding director of the Cornell Program in Infrastructure Policy for Cornell University, says.

“I think the way thinking in the hyperloop space has moved is to get systems operational for freight first, work on these engineering challenges, and make sure these systems are safe before you begin with the challenges of human transport.”

Cargo challenges

Freight presents an easier challenge than passenger services, but there are still possible limitations for companies to consider.

Pneumatic tube systems, which propel containers through a network of tubes using compressed air or a vacuum, are commonplace in healthcare settings. These systems move objects at relatively slow speeds, yet the forces present have been determined to compromise the integrity of blood samples. Moving at fast higher speeds, hyperloop could face a similar problem.

“In the context of freight, you have to consider there is still a limitation on how fast you can accelerate, decelerate and corner when carrying inanimate objects because their chemical composition might change if the forces are too high,” Bailey explains.

But again, before these challenges present themselves, first an operational hyperloop system is required. Engineering challenges aside, there is also the hurdle of urban planning.

If you’re dealing across jurisdictions, establishing a hyperloop route becomes even more complicated.

“It’s very expensive to acquire the right-of-way in the US and there will be a lot of permitting issues,” Geddes explains. “If you’re dealing across jurisdictions, establishing a hyperloop route becomes even more complicated.”

With the challenges cornering poses, hyperloop systems will likely require relatively straight and flat paths, which could limit potential routes in densely populated places such as the UK. Placing routes underground using tunnelling would likely pose less of a political challenge, but could add to the cost significantly.

Of course, these challenges will differ between markets. Virgin Hyperloop, whose sole contract with the Saudi Government intends to connect the western port city of Jeddah with the capital of Riyadh, may have a better chance of success than UK or US-based projects, for instance.

According to Geddes, hyperloop technology is far more suitable for somewhere like the Middle East - which offers relatively level terrain, an abundance of solar power, and relatively ease in acquiring right-of-way.

Sustainability cost

Hyperloop is often proposed as an environmentally-friendly, carbon-free mode of transport. Virgin Hyperloop, for instance, states its systems will have a lower lifetime environmental impact than other alternatives, using 100% electric energy that can be drawn from solar panels covering its tubes.

However, Bailey questions, if it's possible to draw sustainable energy to power a hyperloop, why can’t we ensure that electric trains are drawing energy from a sustainable source instead?

“The question we have with hyperloop is what’s the energy required to create and maintain a vacuum versus the energy required to push that same object through the air without a vacuum,” Bailey says.

Analysis by the US Department of Energy concluded that freight hyperloop transport would be less energy-efficient per ton-mile than all modes of freight transport, excluding air. For heavier freight, the analysis estimates hyperloop would be at least 8x less energy efficient than transport by rail.

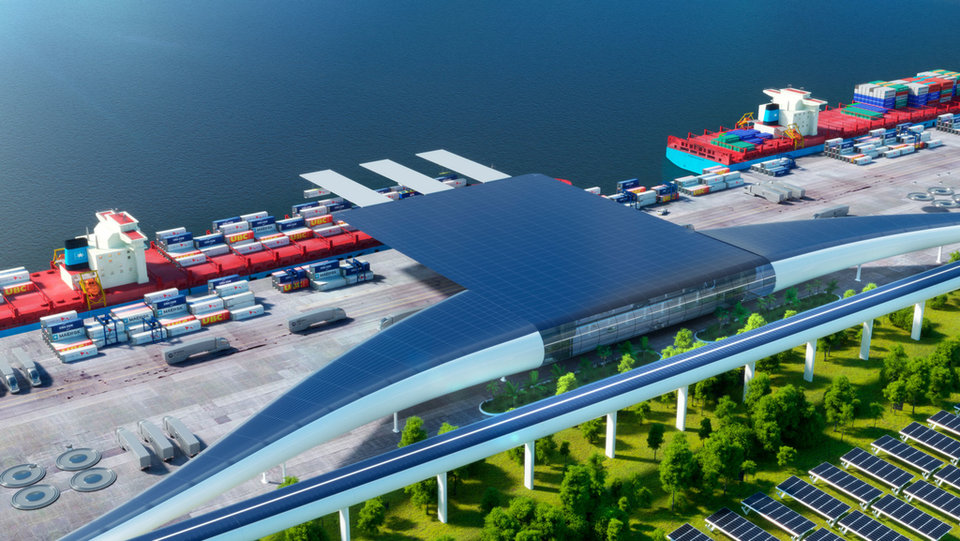

Virgin’s renders show a cargo terminal with renewable energy at the fore. Credit: Virgin Hyperloop

Then there’s the environmental impact of constructing hyperloop infrastructure. This would require a significant amount of concrete and steel, which are high in embodied carbon, as well as vast amounts of tunnelling.

In 2018, Elon Musk’s The Boring Company was forced to abandon plans for an LA tunnel over its potential environmental impact. Likewise, the UK’s HS2 project has been delayed by a constant stream of challenges on environmental grounds, offering a glimpse of the pressure hyperloop projects will likely face just to get off the ground.

“You’re talking about an infrastructure project which is bigger than HS2,” Bailey says. “A hyperloop would need to go underground because the UK is incredibly hilly and also very densely populated, so the environmental impacts of building one of these systems will be far greater than HS2 or another kind of comparable high-speed rail system.”

Will hyperloop play a role in the future of freight?

Hyperloop does have its advantages. If speeds of 760mph can be achieved, it would prove more than three times faster than current high-speed rail systems. Likewise, inside a tube or tunnel, these systems would be less affected by the elements, and should an emergency occur, it would prove far easier to evacuate at ground level than at 30,000 feet in the air.

These systems, Geddes points out, could also offer infrastructure redundancy by feeding utility cables through the tube.

“There are some issues, but I really have confidence that over time, those issues will be addressed,” Geddes insists. “It was 1904 when the Wright Brothers first flew in Kitty Hawk, and look how much aviation has developed in that time.”

It’s not a question of if a hyperloop system will be developed. It’s a question of when.

But will we see the large-scale systems like Virgin Hyperloop has proposed? For Bailey, this is unlikely. Rather, we’re far more likely to see smaller hyperloop-esque systems such as Magway, which push containers through small tubes using magnetic energy.

While this wouldn’t provide the high speeds hyperloop promises, it does offer many of its advantages – a low energy alternative that takes the load off of existing rail and road networks. Likewise, significantly smaller in size, routes could be installed alongside existing transport networks, reducing the environmental cost.

“The cost and feasibility of installing those systems is much lower than if you were talking about a train-sized hyperloop system,” Bailey explains.

“It’s not a question of if a hyperloop system will be developed. It’s a question of when and what that system looks like.”

Main image: John Hammond